The difference between Manager and Director

How leadership focus evolves around What, How, and Why

I was recently asked: “What’s the difference between a manager and a director?”

I answered back then, focusing on the business orientation of the role, operating at a higher level, and redefining how you know if your team is operating well. But the question stayed with me. It’s a good one. The more I thought about it, the more I clarified the mental model I’ve been operating with for years now. One that helped me to grow into the current role and grow a successor who replaced me as a director when I was leaving the organisation.

First, a clarification: when I say “director”, I mean a leader responsible for multiple teams, leading them through other managers. The title varies across companies - it might be Senior Manager, Head of, Group Lead, or something else entirely. What matters is the shift in how you operate, not what’s on your business card.

The What, How, Why

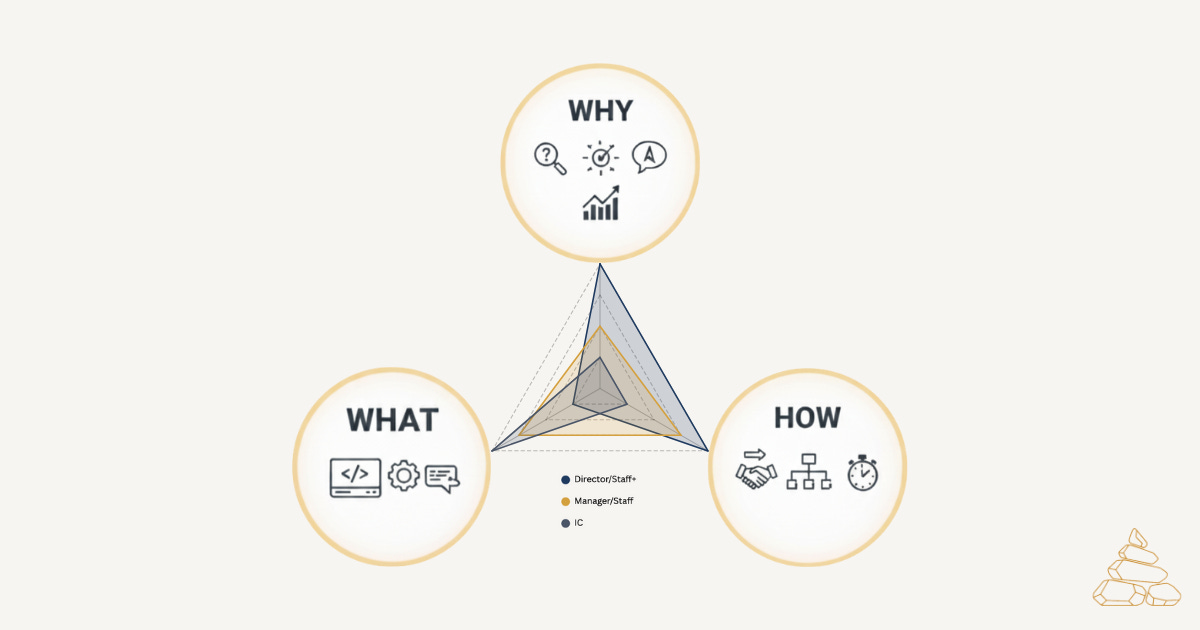

In software engineering, I often refer to the What, How, and Why questions - usually when discussing responsibilities between teams and functions. Product owns the What and Why, Engineering owns the How. That kind of thing. When I thought about the growth from a manager to a director, I realised that the same questions apply. They describe how people’s focus evolves as they progress.

We all start with WHAT - the concrete output we’re working on. A bug fix. A feature. A release. Tangible things you can point to and say, “I did that.”

Then we start looking at HOW - it’s no longer only the output, but also the process. How do we collaborate? How do we make decisions? How do we ensure the quality? How do we ship? Ultimately, it impacts the effectiveness and efficiency of the journey towards delivering the What.

Finally, there’s WHY. The reason behind what we do. The customer and company value. The team’s purpose. The strategy and north star we’re moving towards. This guides our decisions about What to build, and points towards the specific way of How we do it.

Mapping this to people’s growth

Here’s how I connect these three questions to a person’s growth:

Early career Individual Contributor: WHAT is primary. Your value is the code you write, the features you ship, and the problems you solve directly. You should understand the Why, but you’re mostly consuming it from others.

Manager/Staff: You’re still responsible for the What and often even work on it directly. But this is the moment when HOW becomes your primary focus. As a manager, you’re now accountable for how your team delivers - the processes, the collaboration, the effectiveness. As a staff, you’re driving the technical direction, enabling other engineers to work more easily. The greatest impact you can have is making your team deliver better and faster. And you’re evolving your relationship with Why - your perspective widens, you understand more of the context behind decisions and direction, and you need to ensure your team understands the purpose of their work. You’re still primarily a consumer of Why from others, not a creator, but you’re expanding your understanding.

Director/Staff+: That’s when you get even further away from the What you worked on early in your career. You evolve your How from improving a single team and developing engineers, to scaling best practices across multiple teams and ensuring they’re structured in the best possible way. At that time, WHY becomes a priority for you alongside HOW. As a Director, you’re now co-creating the Why with stakeholders - shaping strategy, influencing direction, making calls about where your organisation should focus. The What gets delegated in terms of strict deliverables, and evolves into team topologies, business and technical metrics, and strategy documents. You’re no longer close to the individual features; you’re accountable for the outcomes they produce. As a staff+, you shape the technical strategy, tooling, and architecture across increasing organisation.

Moving forward, I’m focusing on the managerial path because that’s what triggered this thinking, but as shown above, the same principle applies to the IC track. Staff and Principal engineers increasingly focus on improving efficiency of growing organisations, and ultimately implementing and guiding technical strategy - the Why behind architectural decisions, the bets the company should make technically - their What evolves from code to designs to strategy.

From theory to practice

When I answered the original question, I addressed it with concrete examples rather than an abstract definition. The first thing I said was: the director’s role is way more business-oriented. It’s not just execution anymore - it’s understanding how the business works at a deep level, what the direction is in which we’re going, and how tech can help reach those goals.

In practice, this means becoming a strategic filter between business and tech - understanding the business goals and ensuring that technical execution connects to them. And that both the team and stakeholders understand each other’s goals, challenges, and decisions. Similarly, you need to shift your relationship to incoming work. Instead of executing priorities from the above and pushing back only occasionally, you become a filtering layer. You need to evaluate requests to determine how well they align with the strategy, deciding whether they’re something we should do now, later, or never.

Those are examples of owning and co-creating the Why rather than only consuming it. Not waiting for someone to explain the strategy - actively shaping how the organisation contributes to it.

Another angle I picked when answering this question was related to How, in practical terms. With the switch to a director role, you’re further away from the work. You’re no longer part of team meetings, understanding all the project and implementation details, or seeing how things actually get done. You’re not there - that’s not scalable in the long run. You need to learn to collect signals that indicate whether things are going as expected.

For me, that means different metrics like product performance, cycle time, test coverage, incident rates, and more - adapted to the organisation’s context. It means visual management tools that surface what’s happening without requiring me to be in the room. And it means looking across four dimensions I’ve found useful: people, product, platform, and process. If something’s wrong, it usually shows up in one of those.

Aside from that, what helps is getting close to the work that happens. Not all the time, but intentionally doing it from time to time. When I join a team’s meetings for a week or two, combined with skip levels, I get enough signal to understand the situation. If engineers can’t explain why we’re working on this project, not another, or if “on track” is repeated one daily after another and then suddenly becomes “delayed” - that tells me where to work with their manager to improve the situation. And on the contrary, if I see good practices that are not happening in other teams, I can scale them by connecting teams or managers - my position gives me visibility across teams.

Your work with people changes, too. You no longer teach people how to do the job as often as you used to. More often, you teach managers how to teach others to do the job. That’s a different skill entirely.

All this shows how your How evolves.

The power shift

Years ago, when I first stepped into a team lead role, my manager introduced me to a concept from Manager Tools: the three types of power a leader has. Authority (coming from your title and “being a boss”), Expertise (what you know), and Influence (relationships and trust).

Of the three, the power of authority is easiest to understand, but it is the weakest of them all. Whenever you use it, people comply, but only because of your position. Expertise is something you start with: you usually become a lead because you’re good at what you do. People follow you because you’re an expert. And with this, you’re building the third, and most powerful, power: influence. When you build relationships with people and earn their trust, you can get them to follow your lead.

Tying it back to the managerial growth, you start with your expertise. You’re the one who knows how to solve the problem.

As a manager, you start shifting toward influence. You still have expertise, but you’re building relationships, earning trust, and learning to lead through people rather than through knowing the answers.

As a director, influence becomes everything. You must remain technically credible - understand why decisions are made, help to shape them, and set direction, but you won’t have deep expertise in everything your organisation does. Authority remains, as always, but you’re no longer directly guiding people doing the work. There are also other parts of the organisation, and you need them to deliver results. The strongest assets you have are relationships, trust, and the ability to shape thinking. And you do that through influence.

This connects to something David Marquet writes about in Turn the Ship Around - moving authority to where the information is. As a director, you’re not where the information is. Your teams are. Your job is to empower them to make decisions, give them the context they need, and then step back. Support them, but provide them with space to achieve results - and yes, to make mistakes and learn from them.

You can only do that through communication. Clarity on intent. Shared understanding of Why. Trust that flows in both directions.

Communication becomes everything

As you progress, the skills that matter evolve. Early on, it’s hard skills - you write good code, design solid systems, and debug effectively. Then you add people skills and priority management - you coach someone, you decide what matters most. Then, team organisation, stakeholder management, and strategic thinking.

But there’s one skill that cuts across all of it and becomes increasingly critical: communication.

At the director level, communication is the multiplier that makes everything else work. Your influence depends on it. Your stakeholder relationships depend on it. Building other leaders depends on it. Even understanding what’s happening in your teams - reading the signals, asking the right questions - depends on communication.

I’ve seen capable leaders hit a ceiling because their communication didn’t evolve. They could manage a team and deliver outstanding results across the organisation, but couldn’t influence peers. They could execute the strategy but couldn’t shape it because they couldn’t articulate their perspective compellingly, or they were perceived as adversarial rather than collaborative. Communication can become the biggest blocker for growth.

The redefinition of impact

Here’s one aspect we rarely think about upfront: the emotional rewiring required at each transition.

As an IC, your impact is visible and immediate. I wrote this code. I shipped this feature. I fixed this bug. It’s tangible. You can click through it and see if people are using it, looking at metrics.

As a manager, your impact is your team’s delivery. Your people’s growth. It’s indirect, shared, and harder to claim as purely yours. The feedback loop gets longer. I still remember the feeling of being busy all day, not feeling like I was delivering anything or adding value. It only came later when I saw people improving their skills, bigger and more complex projects delivered and used by customers, and teams being recognised.

As a director, it gets even more abstract. Your impact shows up in metrics moving. In business outcomes that are improving. In the increasing organisational capability with a better team structure. The connection between what you do day-to-day and the results you’re accountable for becomes diffuse and delayed.

Each switch requires letting go of the old definition of value before you can fully understand and feel the new one. That’s why it’s painful. You’re not just learning new skills - you’re redefining how you measure your own success.

The further you progress through What to How to Why, the longer the feedback loop on your impact becomes. WHAT is tangible and immediate. WHY is abstract and delayed. Learning to find satisfaction in the latter takes time.

When such transition and evolution don’t happen, you see an anti-pattern: a director stuck in What, remaining on the critical path, either coding themselves or being a review gatekeeper. Or directing the team by saying exactly how the change is to be implemented and not welcoming any challenges. This shows a lack of trust, which harms the team and can lead to growth stagnation and loss of motivation. It also works against the director who gets buried with work they should delegate and is unable to think about the strategic Why.

The advice

No matter where you are on the journey and what your goal is, one actionable piece of advice I can give: engage with all three dimensions early.

The transitions are hard enough without having to build everything from scratch. The leaders who move most smoothly into higher roles are the ones who’ve been developing their relationship with Why, their communication and influence skills for years - not the ones who suddenly try to acquire them when they get the title.

Even as a junior IC, think about why your work matters. Build the connection between your output and its impact on the organisation. Even as a first-time manager, start building relationships with peers and stakeholders.

Don’t wait until the role demands it and position yourself as a natural candidate when the time comes.

Great read, I feel I'm stuck a bit in "IC mode" when it comes to definition - and especially feeling - my impact in "Head of" role, due to direct contribution immediate impact and a fear to loose tech. competence through lack of hands-on work. Thanks for the article - a good goal for this year to re-define the impact and get piece with managerial tasks :-)

Great read thank you! For me, the hardest part for me going from individual to manager then director was continuing to get out of the weeds and trusting my team to handle what I used too.